Recently the Planning Commission convened a series of workshops and an enjoyable public event reflecting on the major planning milestones of the past year. One of the ‘milestones’ identified was the recent boom in very tall (by Vancouver standards) towers with significant architectural pedigrees (many by international firms new to the city). While the planning for these taller buildings has been years in the making (most notably the recent view corridor review and the West End Community Plan), it does seem that we’ve entered a new era of the high design high rise. It is an interesting time for local architecture watchers (did we ever settle on a twitter hashtag? #vanarch?) and some of the towers are extremely compelling. But do they demonstrate exceptional urban design performance?

The principle of ‘urban design performance’ is an important one in Vancouver. Not only is it a standard by which development proposals are judged by (along with many others), the city incentivizes design performance by allowing for increased height and/or density ‘subject to urban design performance’. As a member of Vancouver’s Urban Design Panel (a privilege that I take very seriously), we are often asked to adjudicate development proposals based on urban design performance (although notably, the Panel does not approve or deny approval to projects, it only advises and decides whether it supports or does not support a project). Urban design performance is, to my mind, a very interesting concept in that it is flexible and inclusive, recognizes the variability of sites and neighbourhood contexts. Some of the performance variables are timeless but others evolve with the times (for example, livability or sustainable building performance). Many are well-documented in the City’s policies and bylaws while some are subjective. And one variable I often struggle with is architectural quality.

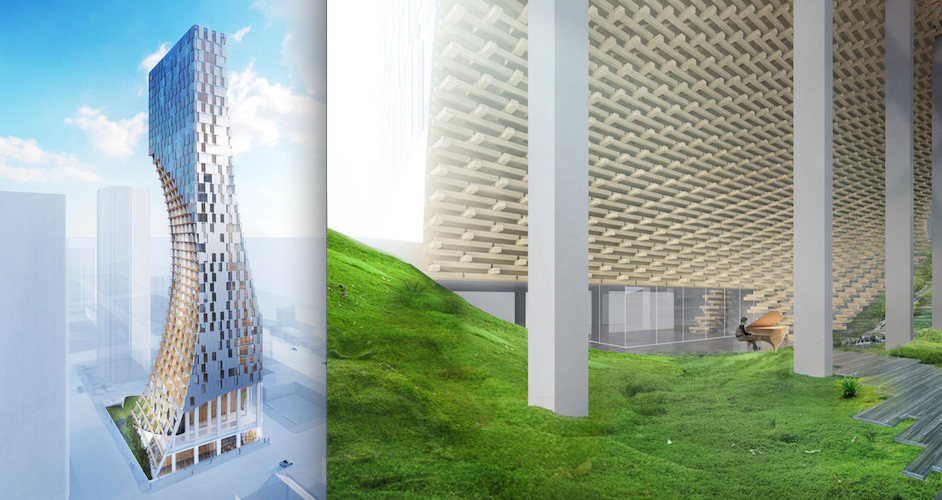

Image: Kengo Kuma / Westbank Projects Corporation (via vancitybuzz.com)

But above all, I want to draw attention to the concept of urban design performance. These towers are only some examples. The bigger question is, what should urban design performance mean for today’s (and tomorrow’s) Vancouver? Should the concept be fixed and timeless or should it expand, contract, evolve for a changing city (and why can’t it do both)? Should the City engage the public in defining urban design performance for a new generation? And what is the relationship of urban design performance to broader City objectives such as Greenest City or the Healthy City Strategy? Personally, I think urban design performance is worthy of a robust public discussion, hence I raise it here. And I would love to know what you think.

Neal, I’ll leave great design to the exuberance of Melbourne. For design performance, I think about the lack of longevity of our strata towers. I live in one, and like it a lot, but appreciate that the model encourages the developer to build as inexpensively as possible while providing expensive-looking surfaces. My long-term concern is energy performance, and I have two issues:

* Every tower build here is full of balconies, and all of them are heat sinks. Because they’re integral with the floor plate of the suite, they radiate heat from the suite during the winter, and draw heat into the suite in summer. Code should require a thermal barrier between balconies and floor plates.

* Why haven’t we adopted light pipes to illuminate interior rooms by drawing sunlight from the building envelope? They would permit far more flexible room layouts, particularly for interior bedrooms and in-suite and interior bathrooms.

You have to wonder, with the starchitect towers, whether the suites themselves are well designed and laid out. Some of the layouts in Vancouver House seemed quite abnormal due to the structural columns needed to support the architecture. Then there’s also the practicality of maintaining the structure, such as washing windows. Shangri-La has a massive window washing crane on top visible for miles around (so does Fairmont Pacific Rim) – both destroy the “look” of the buildings.

One thing I’d like to see is less use of spandrel glass – especially where it appears in near random stripes across a building’s façade (because the architect didn’t plan ahead and interior walls do not meet mullions, like they used to in older towers).

Spandrel is also increasingly used to reduce solar gain by reducing the amount of vision glass (i.e. to create more “solid/opaque” wall). As to that, I’d rather give residents the choice of closing their blinds rather than permanently eliminating the vision glass. It approaches the absurd on Bosa’s University District tower in Surrey City Centre, narrowing what could be expansive walll to wall views to two window panes:

https://flic.kr/p/F9MpWs

Pic by Clement Lee, on Flickr

*********

On the comment of the light pipes, I would rather have shallower floorplates that allow light to naturally penetrate to the back of a suite. The floorplate of the former BC Hydro building (now Electra) resulted in very shallow, very bright condo layouts devoid of hallways.

The larger a floorplate, the more you have expensive square footage occupied by long hallways – especially for corner suites.

Here’s the link to the pic again:

https://farm2.staticflickr.com/1569/25697306490_efa3eaac69_b.jpg

Pic by Clement Lee, on Flickr

WRT the First Baptist Church towers, great tower design!

However, the “garden court” elevator lobbies are really just open breezeways.

Think of the logistics:

– 50 storeys up – what’s the temperature like (in summer and winter)?

– will it be pleasant to wait for the elevator in the wind and rain?

– when heading to the indoor pool or taking out the trash (in winter) – do you bundle up?

– bringing packages or groceries up from the car? will wind-blown rain drench you? will the lobby floor be all wet? will you track water into your suite?

– plus the aforementioned balcony heat sink – that may equally apply to the breezeway slabs.

Have you seen this? Long-term sustainability is dependent on the “lovability” of a building. http://www.originalgreen.org/blog/down-the-unlovable-carbon.html . It would seem to be an argument for timeless design, whatever that is, and is certainly an argument for retrofitting existing buildings that have proved their worth over generations.