This excerpt from an item in The Straight – Vancouver Greens and COPE deliver more detailed housing plans than what’s offered by NPA – raises a host of questions I’ve wanted to ask about the political aversion to highrises in the civic conversation.

.

Certainty for developers and more low-rise density needed, says Green Party Councillor Adriane Carr

“In terms of housing affordability, we can build new housing in the classic model that the construction industry in BC is so good at, and that’s multi-storey, low-level construction,” says Carr.

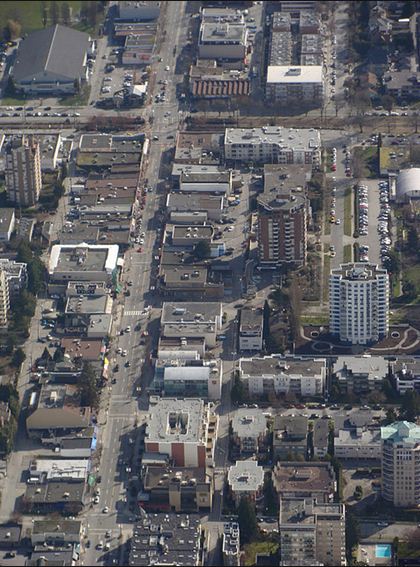

“We need to move on from Vancouverism towers as the be-all and end-all, to multi-storey, low-rise, three- to four-storey construction that is an ideal model advocated by Patrick Condon and UBC’s Design Centre for Sustainability. It can accommodate the city’s growth at lower per-unit cost and not disturb the charming character of our neighbourhoods, plus we have the expertise and this wonderful local sustainable material — wood — right in our own backyard.”

Spreading out density with more smaller, lower buildings along more major routes would also correlate with a city-wide comprehensive public transportation pattern similar to the old streetcar grid system Vancouver started with, rather putting all the “transit eggs in a Broadway subway basket.”

.

A few questions that come to mind – and not just to the Greens.

.

In the last two years less than 15 percent of new developments in the City of Vancouver have been in the form of highrise (13 storeys and above).

Is that too high? Should we say, essentially, no more highrises except in very few places?

What’s the problem with highrises in your mind? Too alienating, out of scale, unsustainable? Where’s the proof – or is your evidence anecdotal?

If we revert to medium- and low-rise development as the new norm, are the loss of views and privacy to the occupants worth the trade-off?

Do people really want to live on an arterial – on a route with busy traffic, more pollution and noise? Is that the only choice they’ll have?

.

.

The unstated assumption is, with new residential density concentrated on the arterial grid, we’re using multiple-family development to shield “the charming character of our neighbourhoods.” That sounds as though ‘neighbourhoods’ are single-family-home in appearance. Apartments and condos are intrusions, best kept to the fringe.

If you live in a multiple-family development, should you expect to settle for a second-class environment in order to protect the first-class neighbourhood for which your building as a barrier?

The old streetcar routes you reference are mostly occupied by low-rise commercial buildings – like Denman, Davie, Commercial, Fraser – with a few suites above the storefronts and the occasional apartment building on the corners. But most of the large streetcar apartment buildings were on the side streets, a block or more from the arterial. That’s where people preferred to live.

The old streetcar routes you reference are mostly occupied by low-rise commercial buildings – like Denman, Davie, Commercial, Fraser – with a few suites above the storefronts and the occasional apartment building on the corners. But most of the large streetcar apartment buildings were on the side streets, a block or more from the arterial. That’s where people preferred to live.

In the best examples – the West End and the Kerrisdale Apartment District – it’s same model adapted to the 1960s: the highrises are on the interior streets, mixed in with low-rises and even single-family houses. Is that unacceptable today? In other words, is the policy intended to keep the remaining single-family-scaled neighbourhoods intact, without the intrusion of any multiple-family buildings of different scale?

mixed in with low-rises and even single-family houses. Is that unacceptable today? In other words, is the policy intended to keep the remaining single-family-scaled neighbourhoods intact, without the intrusion of any multiple-family buildings of different scale?

Is the strategy also to lower amenity in order to encourage affordability? A low-rise on a busy arterial, with less privacy and cheaper design, will arguably be more affordable than a highrise. So if that’s what we build, the city may be a less pleasant place for those residents, but more affordable for them. Is that actually the idea?

How much low-rise development is realistically possible on the arterials given the difficulty of site-assembly? How big is the gap between what is theoretically possible under Patrick Condon’s plan and what could actually be built in a real market?

Are you ruling out very dense development around the rapid-transit stations? In particular, are highrises to be ruled out for the parking lots near stations like Commercial and Broadway?

If you are going to keep the transit hubs low- and medium-rise, at a loss of density to what could otherwise be accommodated within a block or so of the stations – like the Safeway parking lot at Commercial and Broadway – are you prepared to rezone even a few more blocks beyond for low-rise development if it intruded on the single-family scale of existing neighbourhoods?

.

.

So, PT readers, perhaps you have some question – and answers – of your own.

Great post. We will need well planned and well placed high-rise developments if we are indeed wanting to densify the city. I would be curious to see a comparison of unit size, strata fees, price per square foot, etc. for residential towers and low rise buildings.

Yeah, the arterial thing really gets me. I live in the West End just off Denman, and the difference between being on Denman street itself vs being just around the corner on side street is huge. My green leafy block filled with ten story buildings (10! not 3 or 4), is super cozy

The West End/Kerrisdale model is SO much more livable than the “arterial only” model being advocated for eg the Cambie corridor. And it created great neighbourhoods, in both examples. I really wish we could replicated this elsewhere in the city.

Fantastic post.

I think a large part of the problem is that people don’t realise how much of Vancouver is reserved for single-family homes. Most people have little reason to visit the parts of Vancouver away from arterials and downtown, and so they get the impression that apartments and towers are already everywhere.

If you look at a zoning map you’ll note that about 75-80% of our residentially zoned land is reserved for single-family homes and a few duplexes but *nobody* does that. Try asking your acquaintances how much of Vancouver is off-limits to apartments, I doubt they’ll say 80%.

It’s easy to say we should protect single-family neighbourhoods from change when people don’t know that that means banning apartments from the majority of Vancouver’s residential land.

As mentioned by others the West End, Kerrisdale and parts of Kitsilano are what a “streetcar city” really looks like. Ms. Carr needs to find some better advisors.

The main street exists for people to gather and do what people in groups naturally do: watch each other, talk, eat, shop, etc. For a main street to work it must be busier and noisier than anywhere else in the vicinity, but noise and commotion are incompatible with residential uses. Home is where people retreat for quieter, smaller scale gatherings. We must plan to put more low, mid and even high rise buildings on side streets.

Bottom line: people like living NEAR lively streets, not ON them.

Highrises offer views (and block some), minimize ground-level land use, and can be on arterials but removed enough to be pleasant places to live by being vertically separated. Yay.

Highrises also use a lot of concrete which is environmentally costly and a lot of energy which costs both the environment and the home owner. Even discounting the insulation efficacy of walls of glass, the height means greater exposure to heat, cold, and wind, and the elevators and plumbing exert a lot of effort to attain required heights. (And I believe these systems are more expensive to buy and maintain because of their more complex requirements, but I don’t have any facts on that. I do know the fire departments need different equipment for above a certain height.)

So highrises have a great and important place in a diverse housing market especially in a beautiful place like Vancouver. But they get more credit than deserved for environmental and affordability goals, especially as the buildings age.

For an example of high density along but not on an arterial (and I’m sorry I can’t think of a Vancouver example with more low and midrises right now – without the height they blend and are more invisible to sight and memory for those passing along the main drags), in West Vancouver, which is very single detached home oriented overall, there are a couple of streets parallel to Marine Drive in the Ambleside area that are all multi-unit housing. Even some low rises, and single story attached townhomes, but mainly 8-16 stories I think – you could probably rank the buildings by height and end up ranking them by age too with the oldest at the short end.

Low and midrise can be more affordable to build and to maintain than either high rises or detached homes, and can be a buffer from commercial/arterial/highrise/other not-next-door-neighbour factor, and can provide the density that allows transit service and other amenities to serve the single family homes more broadly and affordably.

Wood frame buildings built or renovated to passive house standards with the majority not needing parking or an elevator are a good solution to many housing goals. More of them, in proportion not to exclusion, improves the system for all.

As an owner of many multi-family buildings of up to 4 stories I concur with this view that we could do a lot more mid-rise developments, both along arterial roads as well as in clusters within certain neighborhoods. They are cheaper to build and to operate than a highrise, ideally suited for rental properties or affordable housing that we lack in Vancouver.

If you look at cities that were very dense before the elevator was invented around 1850, say Paris, Berlin, London, Munich, Vienna .. you see essentially ONLY midrise buildings with about the same density of people per acre of land as a 20 story tower with space around it. Vancouver could do that. It does not have to look all like Metrotown, Yaletown or UBC’s Wesbrook neighborhoods with 20+ story towers as the only solution !

I really don’t understand the jonesing for highrises. There are certainly plenty of European cities where midrises surround extremely busy transit hubs.

I challenge most highrise dwellers to recognize, let alone name, the person who lives a few feet away, either directly below or above them.

I think high-rises are not a panacea, the reality is simple: they cost way too much to build. Per square foot of living space, high-rises frequently cost twice as much as mid-rise buildings. The insanely high price of land in Vancouver may level the playing field, but if mid-rise density was suddenly allowed by right across wide swaths of the city where currently only single-family housing is allowed, I think the price of land would collapse because of all the competition between developers that would result.

However, high-rises they definitely have their place in strategic areas. If you want to favor active modes of transport, you need density at the places where most people are going and near transit hubs, the closer, the better, because the farther people are, the more likely they are to drive. If you build low-rise density of 15 000 people per square kilometer but 500-600 meters away from transit and commercial areas, people will likely mostly use cars to get around. That is seen in Montréal where there are some duplex suburbs on the island with respectable density but built around suburban-style commercial arterial that means the closest resident is 300-400 meters away from the arterial or the stores on it. The probability of walking or using transit falls very quickly with distance, so you want to pack as many people near commercial/transit hubs as possible. And high-rises do it well (though by high I mean 8 stories and more, not necessarily skyscrapers). I think you should build all the high-rises that you can sell at these hubs. Because each resident in the high-rises is nearly 100% likely to walk or take transit to most destinations. And transport is the single greatest source of pollution and energy use linked to housing.

People said that people don’t want to live right in the middle of commercial areas. That’s somewhat true, but high-rises are separated from the street by vertical distance. The same reason why some urbanists blast high-rises for cutting the connection between the house and the street makes them very appropriate for busy commercial streets where most people who live on that street WANT to break the connection to get some peace and quiet.

Much of the argument against high-rises seems to turn around “I wouldn’t want to live in an high-rise, so no one should get to live in an high-rise”. I know it’s not for everyone, and I agree with some of the criticism… but I recognize that tastes differ. Some people do crave the isolation and anonymity that high-rise living provides. Who are we to tell them that, no, they don’t have the right to like what they like, that they should want 3- or 4-story buildings with balconies and connection to the street, and that we are going to ban the type of housing they would prefer?

Some spoke of European cities. It’s important to point out that Paris is an exception, it is nearly twice as dense as most other European cities. I prefer looking at Japanese cities, because overall their ridership per km of track of rapid transit tends to be much higher than in Europe, despite subways that are much more expensive to use (there is no such thing as an unlimited monthly pass in Japan, except for a commuter pass that’s valid only between two given stations). Japanese cities also provide much more housing variety to people, unlike the homogeneous European cities. The Japanese cities are chaotic, but there is a logic behind the chaos: they have high-rises at subway stations, and 2- to 4-story buildings on the side streets. Even in cities without subway, you can notice high-rises near the CBD or near malls.

This is the best inspiration I think: high-rises on commercial streets and near transit hubs (which should also have a lot of retail and offices) but build mid-rise and low-rise density around these on the side streets. Vancouver is big enough to satisfy both people who want mid-rise housing and people who want high-rise housing. It’s not an either-or situation people.

Excellent comments, Simon.

I checked your blog and found your comparison between European, North American and Japanese patterns of density very illuminating. Clearly, Condon lets form (i.e. the pre-car and pre-elevator European pattern) overpower function in his proposals about urbanism and transit. We do not have the ancient urban architectural heritage or pre-democracy unifying (and rather absolutist) urban design imposed on many European cities which evolved under the powerful control of elites like Napoleon, Haussmann or the Medicis, so I believe we can afford to study the Japanese model a little closer which places function and efficiency before form. Excellence in architecture can still follow functional programming.

In that light, modifying the low-rise off-arterial development found in the Tokyo neighbourhoods between the high-density transit stations would probably be less of an imposition on the detached house neighbourhoods than mid-rise structures. Well-designed freehold row houses replacing lines of cheaply-built Vancouver Specials would not be as hard a sell as strata four-story walk-ups more than a block off the arterials.

Condon has obviously influenced the Green Party into publishing naïve density policies for arterials that have already been occurring for decades. Four and five-storey buildings with commercial-retail on the ground floor and residential above have been popping up everywhere for generations — and in the complete absence of the cute but deadly and expensive trams Condon promotes that would accomplish nothing more than replicate the existing trolley bus service. In fact, tram service will inevitably suffer due to its comparable inflexibility with congestion and accidents.

What I would change about low and mid-rise development on arterials is pretty simple: Allow a couple floors of office use above the ground-level commercial on the street side, and put the residential on the more livable rear side away from the high-decibel vehicular traffic noise. Should residential be placed on the upper floors of the street side, then step the façade back at that point to create a sound shadow. And give us a lot more accessible, low-floor articulated trolleys with bus stop bulges and signal priority at a tiny fraction of the cost of ripping up the streets and decimating the regional transit budgets for trams that will not improve transit service one whit.

You also posted a study on street setbacks, what gives the street a sense of enclosure and what is merely a waste. Vancouver has a preponderance of 33-foot x 122-foot standardized lots sprinkled with 50 and 60-foot lots. There are 7.4 square kilometres of land locked up in 24-foot front yard setbacks for every 100,000 standards lots. Likewise, there is 1.5+ km2 of land locked in the front setbacks for every 10,000 50-foot lots. Vancouver has lots of land, but obviously it is not used very efficiently.

It’s not like when we *don’t* build housing, the people that would have lived there pop out of existence. We are forcing them to take what would have been their second best choice, maybe involving a longer commute, or a car.

And the debate is always selfishly about “what is best for current residents”. But, as a humanist, I think we ought to eschew this parochial nonsense in favor of “what is best for Vancouver, including her future residents”. If we don’t build the housing people want and that the market demands, we are forcing people out of the city, and into faraway places in housing they wouldn’t otherwise have preferred.

By the way – it’s no coincidence these are the same urban interventionists who presume on people’s transit preferences by advocating for slower, folksier transit they feel encourages a certain lifestyle.

Give the people what they want! Don’t presume on their preferences! People like fast transit and tall buildings; who are we to force them to live otherwise?

It’s informative to read between the lines of what Carr is saying. On its surface, I think most people agree with the idea that we need more low-rise, and that the tower-and-podium model has various shortcomings. But once you start discussing the different possible ways of implementing more low-rise, opinions start to diverge, sometimes widely.

As Gordon and others point out, it’s much preferable to live near the high street than on the high street. I’ve done both and can vouch for the difference in noise and privacy. Introducing low-rise within two or three blocks of commercial storefront has worked well in many parts of the city (Kitsilano, Grandview), but adding more requires upzoning single-family to multi-family. To people who have lived in condos, especially on arterials, the benefit of low-rise beyond the main strip seems obvious. But the council that proposes single-family upzoning will risk an incredible backlash of homeowners accusing them of destroying neighbourhoods. I think this is why many politicians talk about alternatives to high-rise, but no one really does anything. They don’t want to be the one to be accused of destroying neighbourhoods, least of all if they are framing themselves in opposition to other political parties on that basis.

The vast majority of Vancouver is zoned single-family, and growing demographics make upzoning inevitable in our city. Tower-and-podium Vancouverism has almost entirely occurred on former industrial or commercial lots. It has foundered in recent times not merely because the towers are out of scale with the surrounding residential fabric — the same could be said of Kerrisdale, and I don’t hear many complaints — but because upzoning faces such enormous resistance from existing single-family homeowners. Someone with courage (and a mandate) is going to have to take the bull by the horns. The lazy alternative is to promote upzoning along arterials, because future condo-dwellers aren’t in the present to protest whereas single-family homeowners are.

@Chris, it’s a bit of a strange argument to claim that SFH oppose upzoning and densification, when it was those very SFH that fought the city for years by densifying with illegal suites… All of a sudden the planners got religion and decided density was the way to go, but only in the way that suits them. Large developments (such as highrises) bring money to politicians and power to bureaucrats… Letting SFH expand their houses or add additional suites doesn’t, so that’s not allowed. “Family friendly” is only that when large developers are involved.

And note the distinct lack of uproar over laneway houses. The only reason there aren’t more of them is because they’re so expensive to build. The city could have tried to make it cheaper, but that doesn’t suit the agenda. It’s so much easier to pretend it’s the homeowner who’re opposed to densification, when in reality, most neighbourhoods took it on themselves to densify, and would continue to find creative ways to do it if they were allowed.

But no, towers plopped down wherever developers see profits are a much better solution.

Bar, it’s not clear where you are coming from. Other than increasing street parking a bit and having the occasional bad tenant, secondary suites have not fundamentally changed the character of single detached-home neighbourhoods. Low and mid-rises would by replacing housing and decreasing or eliminated the older setbacks, which today may seem overly-generous. That is why alternatives like freehold row housing and small homes on small lots should be introduced first where single-detached on large lots preside. The exception could be a block either side of arterials. Heritage-rated homes (or even non-heritage rated character homes) need protection and upgrading. But they can also be moved around on a property to make room for row houses or low-rise which should take their design cues from the heritage.

I also believe you are wrong about the cost of lane homes. Existing homeowners are not buying the land twice to build them. The costs are related to permits, construction, design fees and taxes, not land purchase. Remember, lane houses cannot be subdivided from the lot and sold, only rented. Yes, there have been some issues with the worst of them, just as there are issues with the blocks and blocks of Van Specials built cheaply and designed by the Vinyl Siding Institute of Architecture. But there are also many, many gems that fit very well into their neighbourhoods. Their benefits include a mortgage-killing second income or a method to keep families in the same home over the generations without having to sell out.

Here’s another post about the sheer amount of single-family zoning in Vancouver, and how it is hindering the provision of new housing:

http://gitanoafricano.wordpress.com/2014/08/05/zoning-its-killing-vancouver/

He’s written a few other interesting posts on similar subjects.

I found it ironic that the author complains about thirtysomethings not being able to afford to live where they work, yet he commutes from Kits to North Vancouver. If you can afford Kits, you can afford North Van.

You found it ironic that the author is self-aware enough to know that he does not represent a whole generation?

I agree with all the points above that there should be more housing in established residential areas. The issue is of course NIMBYism. Maybe there should be a zoning bylaw where the rezoning process is easier if you are only going up one level in density or if you are developing a parcel that is already adjacent to an existing higher density building. That way you can facilitate a more gradual transition and there is less of a shock to existing residents.

Gordon et al:

Since my name is mentioned in your post and you ask questions i will give you the honor of a reply. Below are your questions followed by my answers

QUESTION: In the last two years less than 15 percent of new developments in the City of Vancouver have been in the form of highrise (13 storeys and above).

Is that too high? Should we say, essentially, no more highrises except in very few places?

ANSWER: The question is not how many it is where. In my work with Scot Hein and our Landscape Architecture and Planning students we identified logical places for high rises, notably Cambie and 41st and Cambie and 51st. The intersection of 41st is particularly worthy as it is a reasonable location for a second downtown for Vancouver. See more at: http://www.urbanstudio.sala.ubc.ca/2010/book%20templates.html

My work has been often characterised as “anti high rise”. Not true. For me context is everything, and in the 95 percent of the city that is “flat”, high rises make far less sense than in the downtown or at the key transit intersections mentioned above. Why is this controversial?

QUESTION: What’s the problem with highrises in your mind? Too alienating, out of scale, unsustainable? Where’s the proof – or is your evidence anecdotal?

ANSWER: Like most things in life, nothing is black and white. So highrises are not always good nor are they always bad. However, if you want evidence of the challenges presented by high rise construction we have plenty: Higher per sq foot energy costs, high GHG consequences due to concrete construction, higher per sq foot construction costs, higher vulnerability to earthquake ( see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_tallest_buildings_in_Christchurch ), an unfavorable ratio of land value to hard costs, and concerns about the long range durability of glass building envelopes.

As for questions of quality of life and alienation – that is a journey into the weeds. Suffice it to say that low rise living has its qualitative benefits for sure. They are self evident in the many low rise areas of the city. Kits, the Drive, Main Street, Hastings Sunrise, Victoria, 4th avenue, etc. Again, many of our most favored areas are mostly or all low rise but throbbing with human activity. These are places where resident exhibit very passionate attachment to their neighbourhood. By North American standards they are already high density, at well over 10 dwelling units per acre, the critical threshold necessary to allow for walkability, viable transit, and commercial services within a five minute walk distance.

QUESTION: If we revert to medium- and low-rise development as the new norm, are the loss of views and privacy to the occupants worth the trade-off?

ANSWER: Well, who says we are reverting. I and others are making the case that our continued development of low rise alternatives to high rises solves many problems: lower construction cost, lower energy cost, better relationship to streetcar street commercial (compare street life on Commercial with street life in Coal Harbour sometime) and, of course, less resistance from people in the community. And with the topography of vancouver there are many ways to get views as a big part of the mix: Fairview slopes is probably the best example of this. Privacy? You mean isolation? It can be done in mid rise if thats your desire. I don’t think isolation is what most of us want. I think the ability to isolate is important however. A locked door often does the trick.

QUESTION: Do people really want to live on an arterial – on a route with busy traffic, more pollution and noise? Is that the only choice they’ll have?

ANSWER: Many do. I do. I have lived 8 years now on arterials. First of 4th and now at Alma and Broadway. Very happily. But i object to your characterization of them as “busy, polluted, and noisy”. Your language is instantly pejorative. How about calling them “vital, active and convenient” instead. That has been my experience. In fact I wish they were a bit more vital active and convenient. As for pollution, bus fumes are a problem for units on street facing sides who ventilate from open windows. Lets electrify the transit system. Soon.

Also, sigh, I have never said that all growth should be on the arterials. The same study referenced above showed a variety of house types including townhouses, and, very importantly, an increase in the allowable numbers of dwelling units within the “fabric” of the community back from the arterials. Some of the value of THAT approach can already be seen in the Kitsilano area between MacDonald and Alma, where former single family bungalow structures have been converted into three individually owned strata units. Street activity is high and gardens abound. Vacant units are unheard of. In our study we put around half of all new residents in the “fabric” in expanded and rehabilitated structures – repurposing adapting and reusing the houses on tens of thousands of individual small lot parcels for three four and five dwelling units per parcel. Between this strategy and housing on arterials we were easily able to double the population of the city to 1.2 million.

Patrick, your take on higher energy and emissions per unit area on high-rise vs low-rise buildings seems to be highly selective. More people live in less per person floor areas in higher density communities than in less dense communities. You disregard energy and emissions over the life of the building (or transit mode in previous comments, for that matter). You also do not address using displacements and cleaner energy sources for making Portland cement, and offer only inefficient glass curtain walls as proof of guilt for high-rises while avoiding a plethora of choices in solid panel wall profiles altogether.

What is the best common denominator to make a well-rounded argument, per area unit measures or per capita measures? I believe the latter is the more accurate and useful tool when measuring the short-term construction and long-term performance of cities in almost anything, including emissions and energy use.

In a significant study by two Civil Engineering faculty members and one graduate student at the University of Toronto published in the March 2006 issue of the Journal of Urban Planning and Development (an affiliate publication of the ASCE) the following averaged results for high and low density communities were found for Greater Toronto:

Production:

GHG per person for the production of building materials:

Low density: 30 tonnes

High density: 19 tonnes

Energy used per person (total materials):

Low density: ~360 gigajoules

High density: ~290 gj

Operations:

Annual GHG emissions per person:

Low density: 8,637 kg CO2 / year

High density: 3,341 kg CO2 / yr

Annual energy use per person:

Low density: 85,965 megajoules / year

High density: 40,058 mj / yr

Not surprisingly, higher energy use and emissions were related more to transportation in lower density developments and building operations in high density developments. What was a surprise was that concrete was responsible for only 22% and 16% respectively for per person emissions and energy use from the total of all materials.

Per area emissions and energy use is a useful metric, but it really needs to be put into the context of life-cycle and population. Therein, the perspective is the opposite of your intended results.

… 22% and 16% of high density development …

Did I mention towers supported by cross-laminated and glue-laminated wood instead of concrete?

Just sayin’ there may more than one way to argue against towers, but construction materials, energy and emissions aren’t justified to be on the list.

Gordon,

good for you to once again remind us all of the folly of the parking lot at Broadway and Commercial (and I argued unsuccessfully from within the Province in 96/97 as part of Millenium Line investment that this must change dramatically), we can soon tally 30 years of inaction since the opening of the Expo line. And had the 50,000 residents arrived in this area by now, this could have spurred investment in a westward extension of the line, providing more impetus for densities along Broadway, and at the same time diminish demand elsewhere for development that is harder to serve with mass transit.

But alas, those 50,000 new residents did arrive anyway, and are doing well elsewhere in the region. So might it be useful to expand this dialogue to beyond the rather narrow confines of the CoV boundaries, which is only +/- 25% of region’s population and likely to shrink with time should an aggressive re-development strategy not be pursued sooner than later. As long as inaction occurs within CoV then the mobility challenge gets that much harder to solve as the population grows to the east and south.

btw…we are doing 4 storey residential project in Coquitlam near Vancouver Golf Course on a secondary street, but near an arterial, at 1.85 density. So I don’t understand why this works in Coquitlam, but Business in Vancouver and PT reporting 1.75 on King Edward Avenue in Vancouver’s Kitsilano neighbourhood. And our next project in Langley will be pushing 2.5 near the new Transit center that connects to the Braid Station along the Hwy 1 HOV route.

The world is coming to the region while CoV residents and politicians debate, but will they have a place to live in the CoV is the real question?

Patrick Condon touches on how environmentally unfriendly concrete construction is. I urge posters to watch Sand Wars on Knowledge on October 16 at 9pm,

An overview:

The existence of large tracts of old industrial land around False Creek essentially bought Vancouver 30 years in which it could grow without fundamentally tackling the challenge of densifying the 80% of the city that is essentially suburban. I have always thought that Kerrisdale offered a made in Vancouver model of a walkable, mixed use, compact, transit-focused, community that includes a variety of housing forms both ground oriented and high rise, along arterial roads and on quieter side streets, that could be replicated throughout the city at major arterial nodes. This means that the question that was dodged in the old CityPlan process (mapping those proposed village centres) has to be addressed. I thought that Oscar Newman essentially answered the question on whether high rises were a good form of housing in the 70’s (it depends on your lifestyle and where you are in the lifecycle). I would like to see a mixed housing form model that includes high rises, mid-rises, house conversions and a personal favourite, fee-simple row houses, that accommodates all lifestyle preferences in close proximity. This would mean that over time the percentage of Vancouver devoted to suburban style single detached housing will decline and be replaced by relatively dense, mixed housing walkable urbanism. This is a process that could address Vancouver’s growth for decades to come incrementally and not on the basis of master planned mega-projects for the most part. It is conceivable that Vancouver could grow to a population of 1 million in this way in a form that would feel entirely familiar.

Mark Hornel hits the nail on the head. Vancouver needs a broad range of housing typologies and tenure models (including the ‘fee simple’ and/or long-term leasehold row housing that works so well in London, New York, etc.). Patrick Condon also gets it right when he notes that both low- and mid-rise housing forms can be inserted into the typical Vancouver single-family housing fabric without fundamentally changing the character and scale of these cherished neighbourhoods, and that high-rise forms should be concentrated at key transit nodes (such as Commercial & Broadway, for example, or Cambie & 41st). It is not an ‘either (high-rise) or (low-rise)’ solution, but rather ‘both/and’, largely depending on context.

Densification – if we can agree that this is a good thing in support of more sustainable, more vibrant, less wasteful cities – can take multiple forms, as many have noted of European and Japanese cities. As Mark notes, the CoV has picked most of the low-hanging fruit (i.e. former waterfront industrial and railway lands) and is now facing the much more challenging and complex process of intensifying our single-family neighbourhood fabric, which still makes up the vast majority of the city’s residential land base. A carefully planned (what a notion!) rather than simply site-opportunistic mix of higher-rise at key transit nodes, mid- and low-rise (say 4-8 storeys) along and near major arterials, and a wide range of ground-oriented intensification typologies (e.g. duplex, triplex, townhouses, row-housing, zero-lot-line courtyard housing, laneway houses, mews, lofts, narrow lot [e.g. 16 ft and 25 ft] housing, etc.) within the single family neighbourhoods, will accommodate the City of Vancouver’s fair share of the anticipated regional population growth. But the devil, as they say, is in the details, and we need comprehensive, equitable planning. ‘Spot rezonings’ for much taller projects that are totally out of context with their immediate surroundings are absolutely not the way to go (Mount Pleasant’s Rize project comes to mind), and will only guarantee continued community resistance and increase people’s cynicism in local politics and neighbourhood planning processes that ’embed’ certain landowners’ future densification aspirations. The ongoing proliferation of so-called CD-1 rezonings across the city are a symptom of the problem.

Well said !

Both Patrick and Lance seem to be reflecting positively on former Director of Planning Brent Toderian’s “corridors and nodes” approach as a structuring concept for a citywide plan. Brent demonstrated what he had in mind on Cambie Street – a 6-storey corridor with nodes of intensive development at key transit hubs – e.g., Marine Drive and Oakridge Centre. And also in Norquay Village, but with a wider corridor not limited to Kingsway frontages alone, and with transitional densities off the arterial. A great mix of housing types.

As said above, the devil is in the details – how wide is the “corridor”, how high is the “node”? Answer – it will vary from place to place, but will tend to look either like Cambie Street or Norquay Village, or some combination of both. (In my view it was a lost opportunity to do something reasonable in Marpole, given resistance to off-arterial … townhouses.)

In my view, the nodes will almost always be site-specific rezonings, or CD-1s in Vancouver plannerese. And generally taller and denser than their neighbouring areas, in order to support transit and to deliver as many community benefits as can be reasonably negotiated. Again, how tall is tall will have to be determined through a balanced community process, informed by excellent urban design professionals. Either of these without the other is not a valid or supportable approach any more, if it ever was.

If someone has a widely differing but equally compelling,understandable – and implementable – concept this would be a good opportunity to put it forward. (Is Nouveau Paris achievable here? Can Kerrisdale or Kits be transplanted elsewhere in town? Should the Flats be built to accommodate almost all future development, as another recent Director of Planner has suggested?)

Yes wood-frame buildings are more cost-effective to produce in the short run, but if we are really trying to be green, in the long run, a concrete structure can last 1,000 years or more whereas a wood-frame structure is pretty much done at the 60-year mark. Fine for our typical North American, short-term way of thinking, but there is a reason most buildings in Europe are built of stone or concrete and not wood. There they look at structures with a multi-generational, 300-year time horizon. That’s a sustainable approach to building.

In sharp contrast to here, where a 3-storey wood-frame structure is just a temporary placeholder, waiting to be replaced with a new concrete mid-rise or high-rise. How many concrete buildings in Vancouver have been demolished in the city’s history? I bet you can count them on one hand, maybe two. Versus the 2000+ wood-frame structures that meet the landfill every year in our region.

Yet the Greens would have us build, in relative terms, disposable wood-frame structures. It is not a reasoned, sustainable approach, but a shallow, populist position designed to get votes from the NIMBY’s. I have never seen someone as anti-sustainability as Adriane Carr. Disgusting. Whatever the political equivalent of corporate greenwashing is, that is what she is. Makes me sick.

I would say you are being overly optimistic that the concrete buildings in Vancouver are going to last 1,000 years. If I am not mistaken, the figure bandied about is more like 100. The Colliseum they aren’t.

Not the entire building, but the concrete structure, if properly maintained (i.e. protected from water ingress), can basically last forever. Concrete gets harder and stronger as it ages. There is no reason why a concrete structure can’t last 1000 years. Windows, mechanical systems, elevators etc would all have a shorter lifespan, of course, and would have to be replaced at regular intervals over this period. But the structural elements of a concrete building could endure for centuries.

People have to realize that only more supply cause prices to fall, or shall I rather say, to rise less. Anything else, especially restricting supply or creating even more rules around it, will make housing even more expensive.

Why is no candidate saying that ?

Why is no candidate offering Langara golf course as a new park plus new affordable housing ?

Why is no candidate suggesting building more towers along Broadway subway, say 20 stories ?

Why is not candidate suggesting creating more land, say off Spanish Banks or off Coal Harbor or off the Fraser River or west of Richmond in the mudflats ?

Why is no candidate suggesting to annex Burnaby, Delta, N-Van, W-Van and Richmond and creating more housing in the new “Vancouver” ?

Why is no candidate suggesting to build mixed use high rise housing in East-Van right besides downtown, to solve the homelessness problem and to get private money build more housing close to downtown ?

Lots of great outside-the-box ideas there.